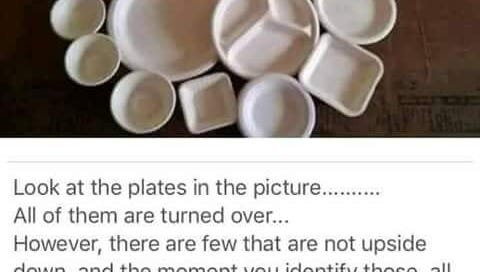

Someone sent this to me on Twitter:

When you first see the plates upside down, and then notice one right-side up, suddenly they all appear right-side up. The same happens in reverse.

In a way, this mirrors how an editorial cartoon can work when it holds two meanings—once you catch one, the entire perspective shifts.

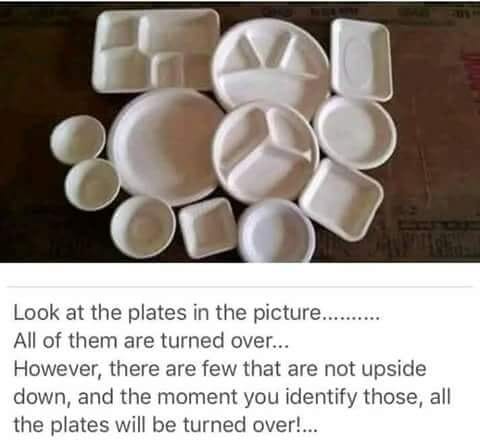

In 2003, I drew a cartoon of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien (1993–2003) posing like a bodybuilder, flexing imaginary muscles while wearing nothing but a Speedo. I assumed the most controversial part of the cartoon would be depicting Chrétien nearly naked. My editor at the time, Bill Turpin, seemed to agree—but despite his reservations, he let it run. Bill wasn’t one to censor cartoons; he, like all great editors of that era (and few today), believed that a sharp, edgy cartoon was essential to a newspaper's voice.

The next day, emails and letters to the editor started trickling in. There weren’t many, but the outrage was unmistakable. People were shocked that the cartoon had been published at all. Turpin called me in to talk about the complaints, and neither of us could understand why a simple drawing of someone in their underwear had sparked such fury. It didn’t seem like the kind of thing that would cause this level of backlash.

The mystery lingered for two years—until one day, while revisiting my old work, I stumbled upon the cartoon again. With fresh eyes, I finally saw what those angry readers had noticed. It was like the optical illusion with the plates—everything flipped over, and suddenly I saw the cartoon in a completely new way.

The outrage two years earlier wasn’t about Jean Chrétien in his underwear. They saw something I never intended.

Instead of seeing Chrétien flexing his muscles, they saw him, well... "stroking" a very different one.

I was stunned.

Suddenly, all those complaints made sense. No wonder people were so outraged.

It did not help that it said that he was exercising his soft power.

And just like with the plate illusion, once you see Chrétien doing something I never intended, you can’t unsee it—no matter how hard you try.

Fast forward to last Friday.

It was a busy day, and I needed to come up with a quick idea so I could get two cartoons finished by 5 p.m.

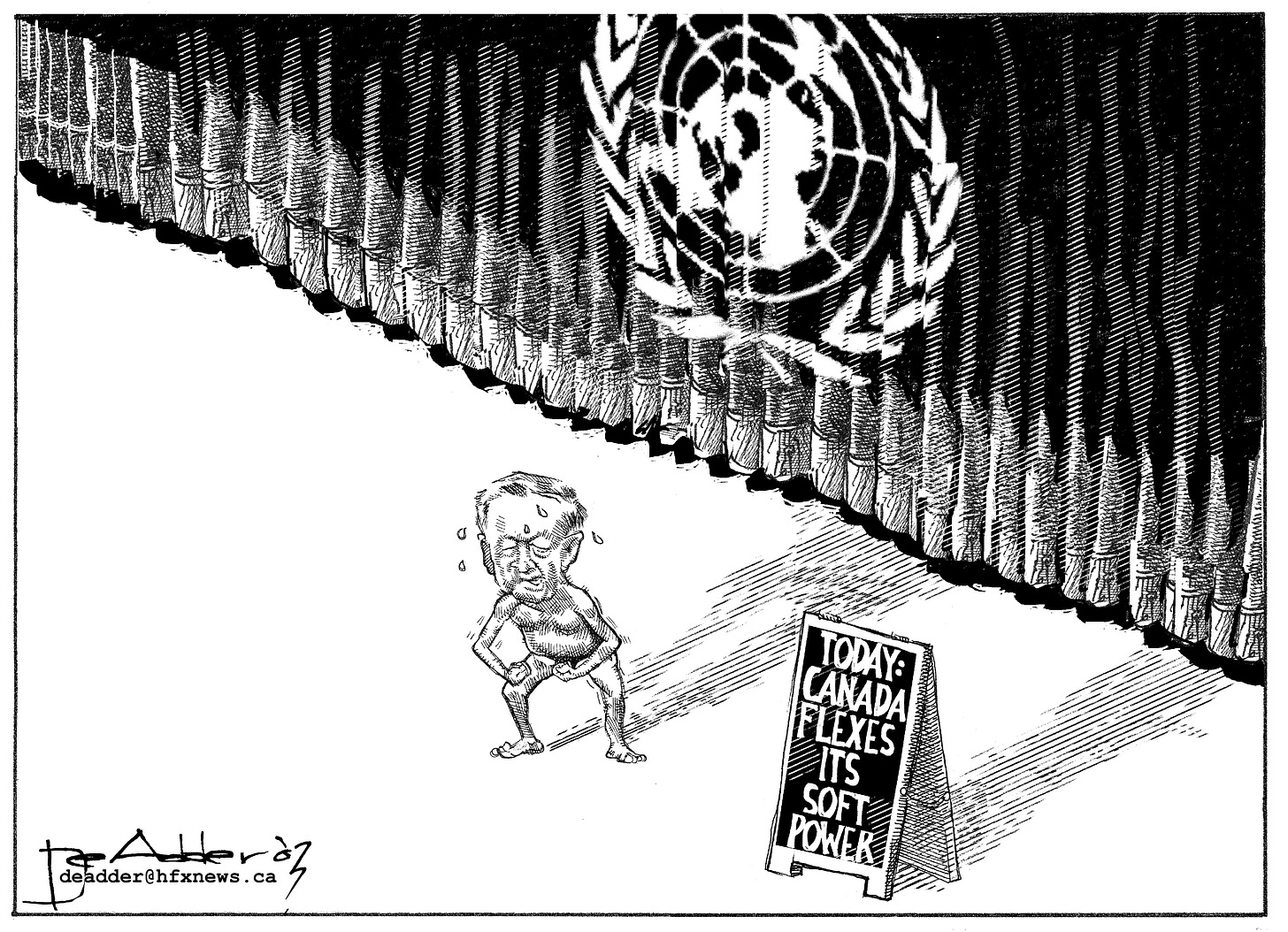

I remembered that a lot of people were running for mayor, and it reminded me of an old cartoon I had drawn when too many people were running for Liberal leader. In that one, I sketched a man labeled "Everybody" talking to a monkey labeled "his monkey," with the caption, “Hey, I’m also running for Liberal leader.” The joke was clear: everybody and their monkey were throwing their hat in the ring.

I figured I could reuse the same joke for Halifax’s mayoral race. First, I counted how many candidates were running. Only the top three stood out, while the rest were mostly unknowns, with a couple of familiar names. I tallied 16 candidates. In all my time in Halifax, I’d never seen more than six people running for mayor at one time.

So, I drew the cartoon and moved on to the next one. I didn’t think it was great, but it seemed good enough for the week.

What I didn’t realize was that one candidate, Darryl Johnson, had joined the race late. Johnson is a community specialist with Halifax Public Libraries, bringing 30 years of experience working with youth. He also happens to be Black.

When Johnson saw the cartoon, he didn’t see it as a critique of the number of candidates. Instead, he saw it as an attack on him—a Black candidate running in a predominantly white campaign. He saw everybody as the white candidates and the monkey as him.

Unfortunately, once you see the cartoon through Johnson’s eyes, it’s hard to interpret it any other way.

I had no intention of targeting Johnson with the cartoon, but I now understand why many people perceive it differently. I did apologize to Johnson and explained that it wasn’t about him.

I wrote this column in Substack for the people and electors of Halifax, and I want to make it clear that Johnson wasn’t overreacting or using this situation for political gain. He had every right to believe the cartoon was about him, and in fact, the Black community has a valid reason to feel the same.

Centuries of discrimination and racism towards the Black community create a strong argument that this cartoon could be seen as targeting Johnson, even though that wasn’t the intent. When considering candidates in the upcoming election, Johnson should be viewed as someone with legitimate concerns about the cartoon that appeared. History has taught us that he was justified in questioning its message, even if no harm was intended in this case.

He should not be looked upon as anything except a person who had valid concerns about something in this community newspaper. Johnson’s concerns were real, even though they turned out to be false.

The comments so far as awesome. Thank you.

Recently retired middle school counselor here. We had a wonderful woman as our head custodian, she loved the kids but would get on them when needed. She would frequently refer to them as “monkeys” or “little monkeys.” This woman is from Romania and I felt the need to invite her into my office and explain why we don’t the word monkey to refer to our kids. She was absolutely aghast. I also explained I knew she was not aware of our special American brand of racism, that’s why I explained it to her. She thanked me and never used it again. To be fair, sometimes kids are referred to as “monkeys” meaning they’re chattering a lot or bouncing around a lot or whatever. But to be safe, we educators NEVER use the word to describe people.

I really appreciate your acknowledgement here. As Maya Angelou says “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

As always, we love your work!